Salt and Battery

I like to consider myself fairly well informed, but often I find that I am ruinously ignorant about things both ubiquitous and consequential. Wandering about in the snow recently, simple road salt began to fill my mind with questions as I watched it being flung about by Municipal worker and home owner alike as a prophylactic…

I like to consider myself fairly well informed, but often I find that I am ruinously ignorant about things both ubiquitous and consequential. Wandering about in the snow recently, simple road salt began to fill my mind with questions as I watched it being flung about by Municipal worker and home owner alike as a prophylactic against ice. According to Smithsonian Magazine, 137 pounds of salt are spread on the nation’s roadways per every American.

From Wikipedia:

Halite occurs in vast beds of sedimentary evaporite minerals that result from the drying up of enclosed lakes, playas, and seas. Salt beds may be hundreds of meters thick and underlie broad areas. In the United States and Canada extensive underground beds extend from the Appalachian basin of western New York through parts of Ontario and under much of the Michigan Basin. Other deposits are in Ohio, Kansas, New Mexico, Nova Scotia and Saskatchewan. The Khewra salt mine is a massive deposit of halite near Islamabad, Pakistan. In the United Kingdom there are three mines; the largest of these is at Winsford in Cheshire producing half a million tonnes on average in six months.

I can tell you, categorically, that my little dog ain’t too happy with the salty sidewalks. It hurts her feet and the chemical action of the brine dries out her pads. A personal endorsement for a product called “Mushers Wax” is offered, based strictly on one dog and a highly non-scientific clinical trial. It’s a sort of wax which is supposedly used for working sled dogs in Alaska, and it seems to make my quite urban and extremely unemployed dog a lot happier when marching about on salty pavement.

The side of me which hangs around Newtown Creek and the environmental crowd wonders about the effect that the saline rich waste water will have as it discharges from the 400 Combined Sewer Outfalls found along the harbor, and seeps into the already brackish waters of NY Harbor. Melt water, on a citywide basis, produces billions of gallons of largely untreated wastewater which carry the tonnage of spread salt into the water – producing what is known as “salt shock” in marine organisms.

How many tons of dissolved salt does this melt water carry, and how does that affect both the physical geology of the harbor and the estuarine life contained within?

From saltinstitute.org:

Will we run out of salt?

Never. Salt is the most common and readily available nonmetallic mineral in the world; it is so abundant, accurate estimates of salt reserves are unavailable. In the United States there are an estimated 55 trillion metric tons. Since the world uses 240 million tons of salt a year, U.S. reserves alone could sustain our needs for 100,000 years. And some of that usage is naturally recycled after use. The enormity of the Earth’s underground salt deposits, combined with the saline vastness of the Earth’s oceans makes the supply of salt inexhaustible.

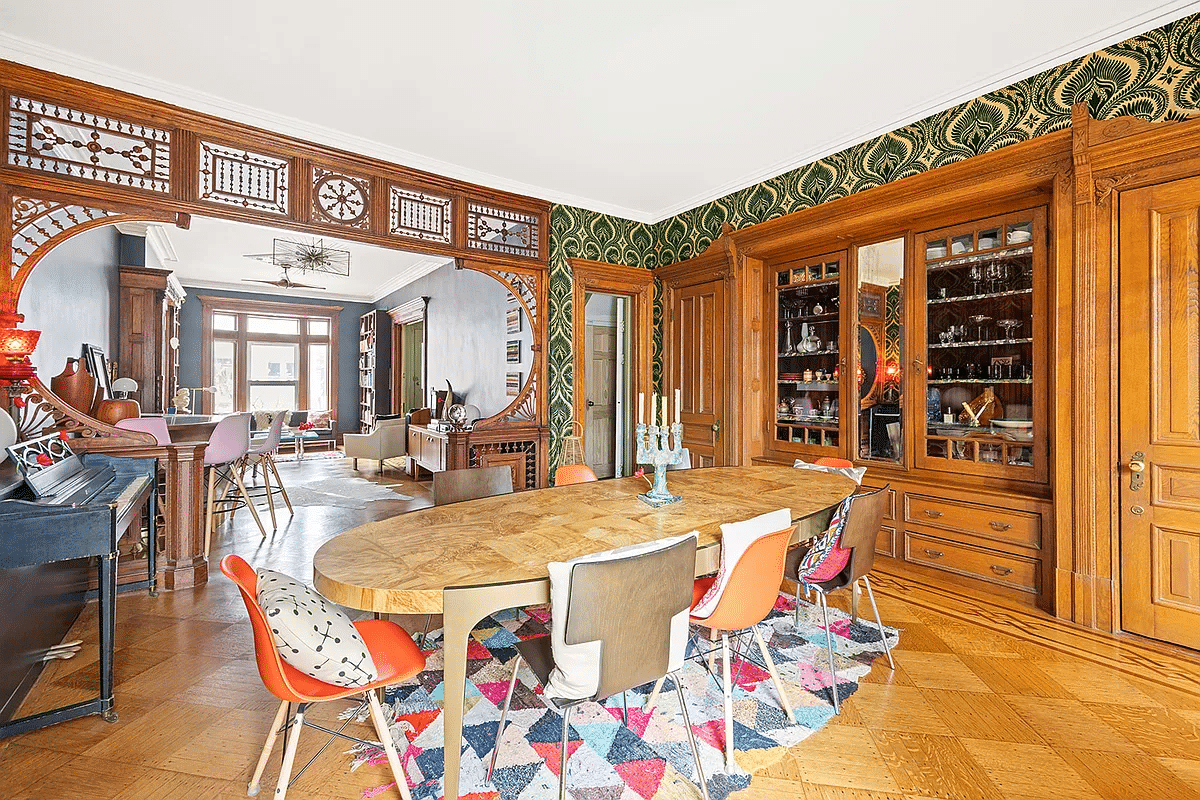

Pictured above is the titan Atlantic Salt facility on Staten Island, one of many such bulk storage depots which stockpile the stuff for weather emergencies. Realization that I have no real idea what road salt is (other than its purely chemical makeup), how it might be quarried, and what the difference is between table and road salt forced me to begin reading up on this subject.

A similar intellectual journey involving honey grasped me several years ago, it should be mentioned.

From Wikipedia:

Refined salt, which is most widely used presently, is mainly sodium chloride. Food grade salt accounts for only a small part of salt production in industrialized countries (3 percent in Europe) although worldwide, food uses account for 17.5 percent of salt production. The majority is sold for industrial use. Salt has great commercial value because it is a necessary ingredient in many manufacturing processes. A few common examples include: the production of pulp and paper, setting dyes in textiles and fabrics, and the making of soaps and detergents.

The question, for me, isn’t “How do you acquire salt (or honey)?”.

It’s “How do you acquire salt in industrial level quantities?” The honey question led me down a rabbit hole which exposed a complicated story of international trade, prehistoric industrial development, and the realities of how fragile the agricultural system actually is. Also, that honey is heavier than water and great care must be exercised when shipping quantities of it by sea.

Salt is another ancient industry, and was a substance worth more than its weight in gold during Roman times.

According to Roman Historian Pliny the Elder, the soldiers of the Republic were originally paid in salt, which is where the term “Salary” was coined (or Coine’d).

From Wikipedia:

Prior to the advent of the internal combustion engine and earth moving equipment, mining salt was one of the most expensive and dangerous of operations. While salt is now plentiful, before the Industrial Revolution salt was difficult to come by, and salt mining was often done by slave or prison labor. In ancient Rome, salt on the table was a mark of a rich patron (and those who sat nearer the host were above the salt, and those less favored were “below the salt”). Roman prisoners were given the task of salt mining, and life expectancy among those so sentenced was low.

Newtown Creek Alliance Historian Mitch Waxman lives in Astoria and blogs at Newtown Pentacle.

What's Your Take? Leave a Comment